Photo by Martin Dee

Brittney is a proud Heiltsuk artist, educator, and PhD student deeply committed to sharing her culture through art and education.

Through her work, Brittney integrates traditional Heiltsuk practices such as Formline Design with contemporary approaches to learning. She is passionate about creating spaces where children, educators, and community members, from ages three to Grade 7, can connect meaningfully with Indigenous teachings.

We spoke with Brittney about the woodcut artwork she contributed to the Indigenous Symbols and Signifiers initiative, which asked: What symbols represent belonging in your culture?

About Brittney and her inspiration

My mother, Clarissa Feiertag (maiden: Reid), was born in Bella Bella, British Columbia, and attended the residential day school there. When she was around nine, she and her family relocated to Steveston. Growing up, I learned about my grandfather’s life as a commercial fisherman and how deeply connected he was to the water. Those teachings from Bella Bella—about land, sea, and family—continue to anchor my work as an educator.

I completed my Bachelor of Fine Arts at UBC, where I focused on painting and installation. I explored ways of making Indigenous knowledge visible through a teachable lens, including a project designing underwater sculptures for the Vancouver Aquarium. That process deepened my reflection on how art can be a vessel for cultural learning.

When my mom passed away in 2013, I stepped away from painting and creating. It wasn’t until I became a mother that I returned to art with a renewed heart. I wanted my daughter, Liv, to grow up with stories, shapes, and teachings that would root her in love and identity.

Brittney's artwork

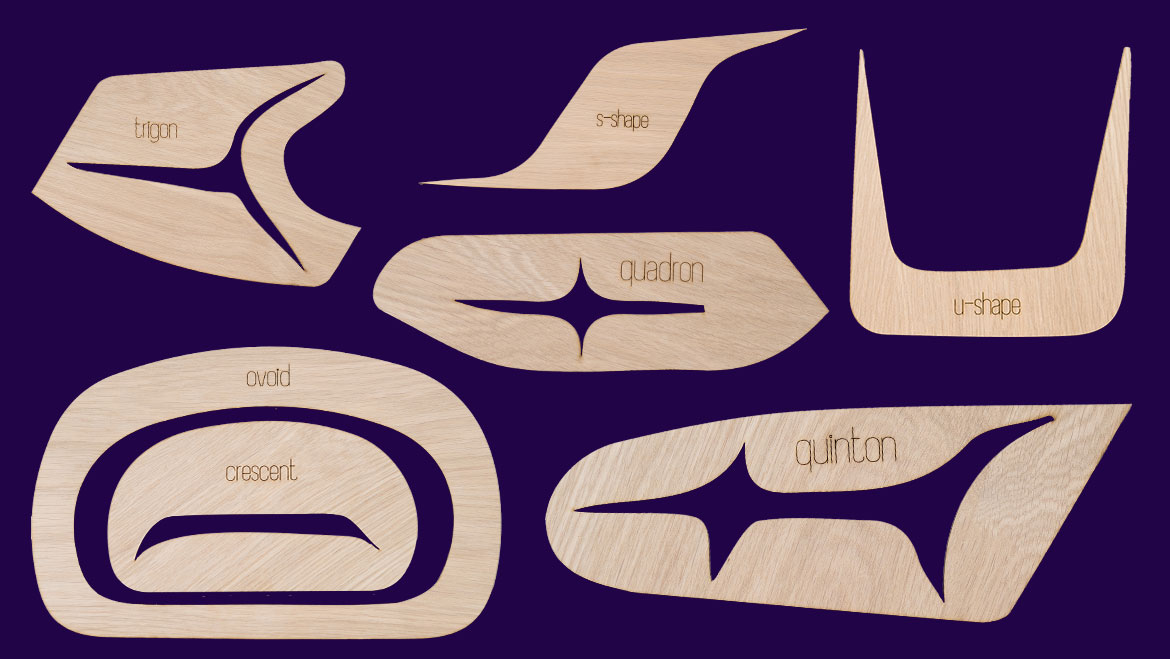

Laser wood cut artwork created by Brittney that highlights basic Pacific Northwest Coast Formline shapes

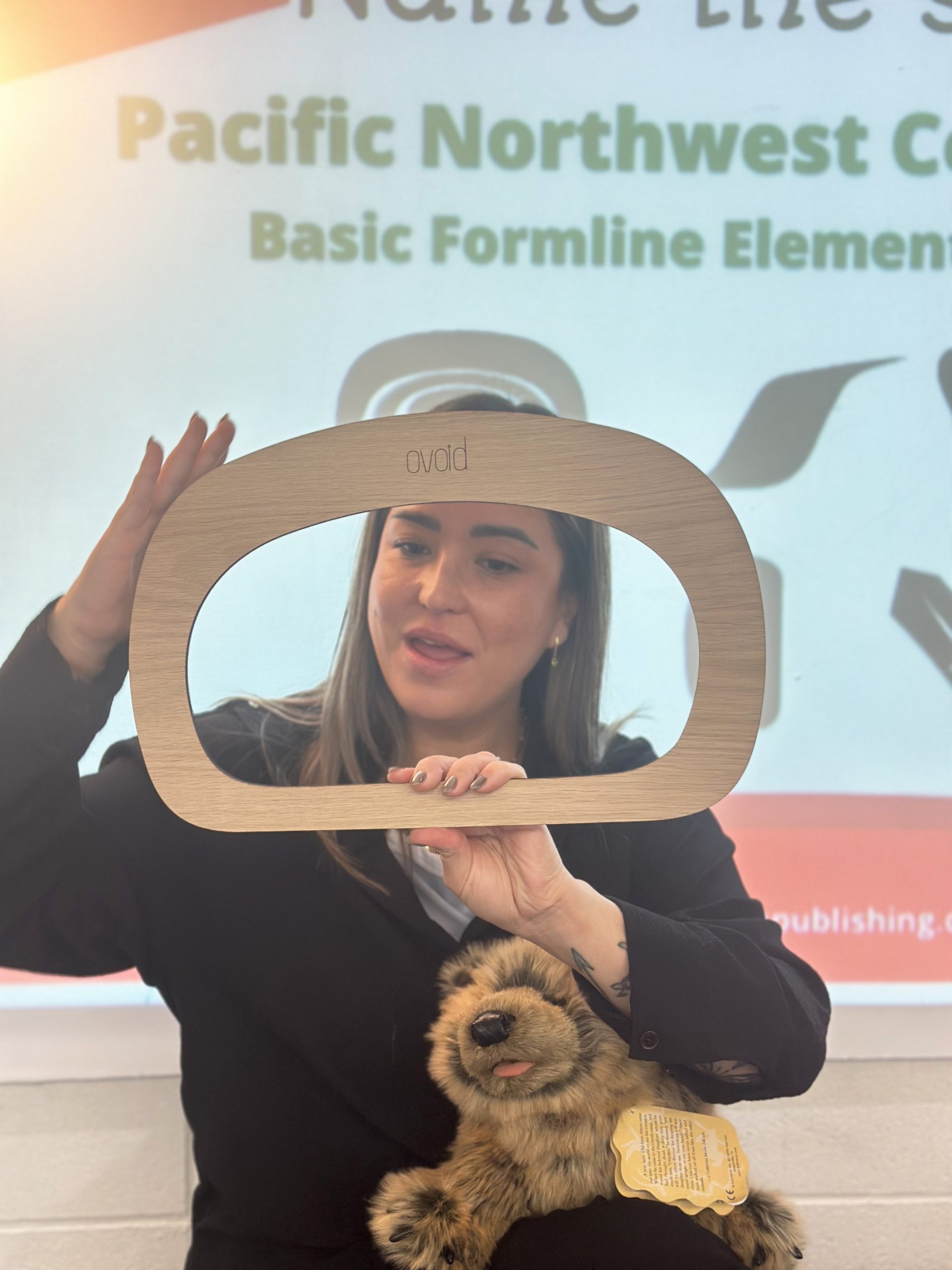

Brittney showing the Ovoid shape

Brittney teaching basic Formline elements and shapes in the classroom. Photo provided by Brittney

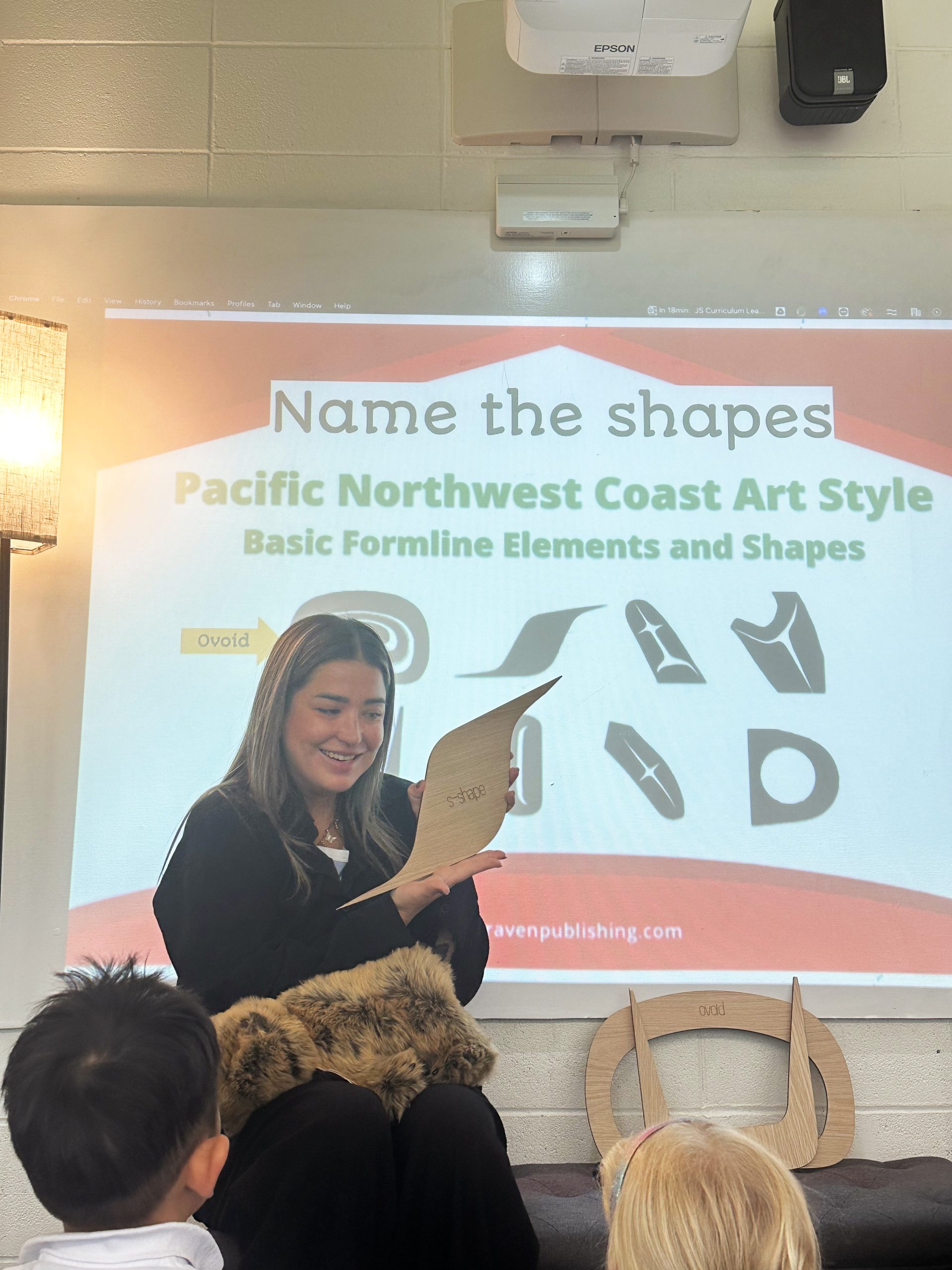

Brittney showing the S-shape

Brittney teaching basic Formline elements and shapes in the classroom. Photo provided by Brittney

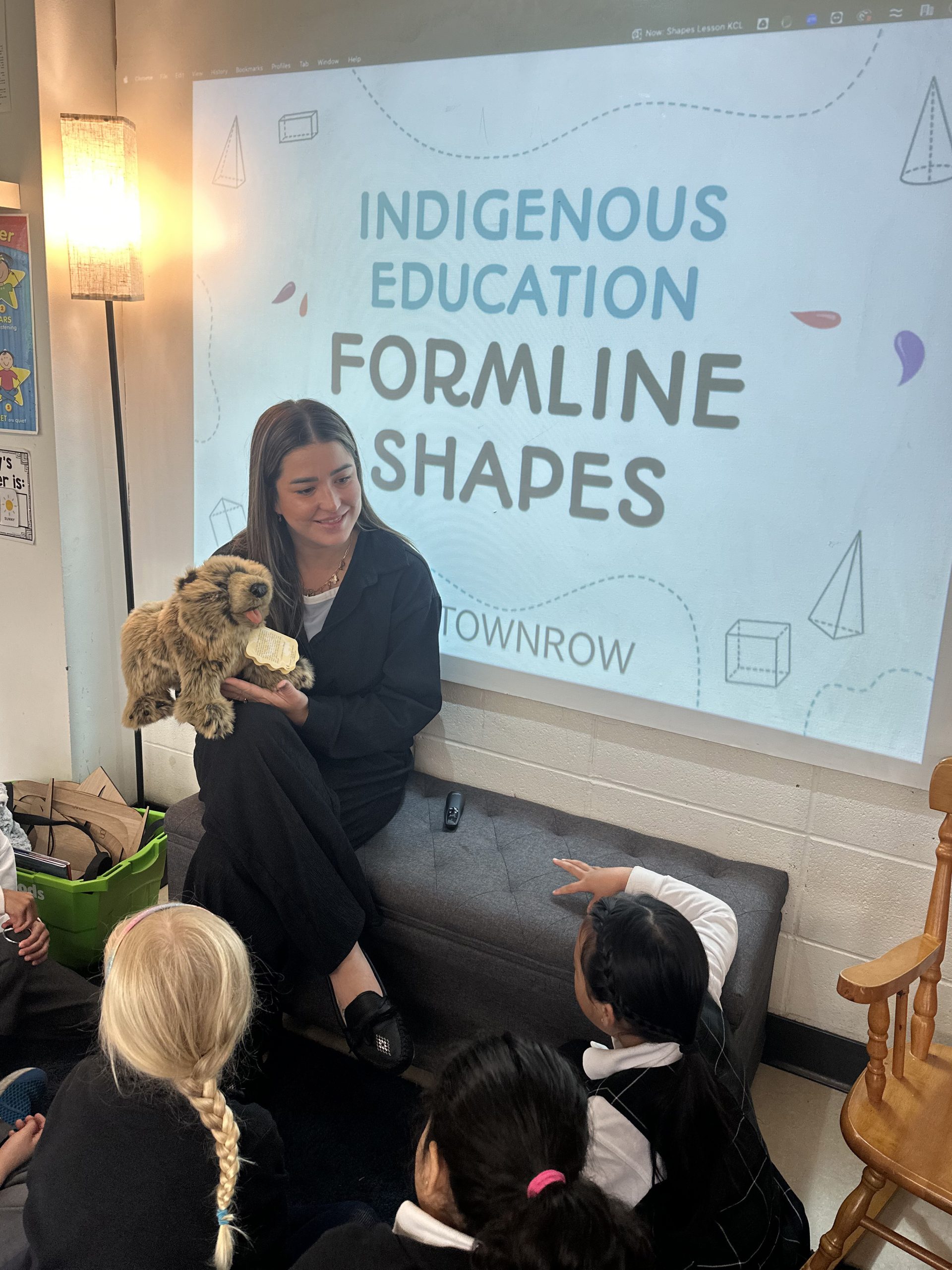

Indigenous Education: Formline Shapes

Brittney teaching basic Formline elements and shapes in the classroom. Photo provided by Brittney

Land-based memories from Bella Bella

Some of my most vivid memories are from time spent in Bella Bella—scraping barnacles off my grandfather’s boat, learning to fish alongside my grandpa, Percy Reid. I remember the first time I joined my grandfather on the open ocean: a massive boat, the waves beneath us, and fish bigger than I could hold. I must have been around ten. The teachings from those trips—about patience, responsibility, and the rhythm of the tides—stay with me.

Whenever I share stories with my students, I invite them to locate Bella Bella on the map. “Imagine heading past Vancouver Island, north along the coast, almost to Haida Gwaii,” I tell them. These land-based stories are more than memories—they’re teachings I carry into my classroom every day.

“For me, art is a way to pass on teachings, deepen our connection to land and culture, and create joyful learning spaces. These shapes hold more than lines—they carry language, memory, and story.”

Teaching formline as a shared language

Ovoid wood cut by Brittney

At the heart of my art practice is Formline Design, a traditional visual language from the Northwest Coast, including the Heiltsuk Nation. For the Indigenous Symbols and Signifiers initiative, I created a series of laser-cut wood shapes—Ovoids, U-shapes, S-shapes, and more—that I use in my teaching practice. Each shape is engraved with its name, inviting learners of all ages to build a shared vocabulary around Indigenous art.

I work at an independent school near UBC, supporting students from junior kindergarten through Grade 7. I use the same shapes with our three-year-olds as I do with the sevens. That consistency matters—it builds connection and understanding across age groups.

Importantly, I also teach students about where these shapes come from. I explain that while Formline is from my home community, we live and learn on Coast Salish territory, where the visual language is distinct. Too often, Indigenous art is flattened into a single image—like totem poles—when in fact, each Nation has its own stories, practices, and designs. I see it as part of my work to help students recognize and respect those differences.

A lot of the knowledge I share comes from a website that talks about Formline art. It discusses the Ovoid, its shape, and its significance. I share those teachings with my students, too. It’s all teacher resources you can use in the classroom.

Shapes with meaning, stories with heart

Quadron wood cut by Brittney

I tell my students to think of these shapes as having points—especially the relief ones. I show them how the ovoid is a solid piece, and then explain that relief is what happens when we carve into that shape. The relief lives inside the shape. I’ll ask, “How many points do you see here?” They’ll say, “Five.” Then I bring out the Quadrant, which has four points, and the Quinton, which has five.

Students who love math get especially excited about this. We talk about how Quinn and Quinton connect to five, and quad connects to four. It becomes this playful, memorable language that bridges art and numbers.

Trigon wood cut by Brittney

Next is the Trigon—a shape with two or three points. I tell the kids to think about triangles, something they already know. From there, we build new understandings together. I show them that this shape might represent something like an orca whale, and we count the points—one, two, three. That’s a Trigon. Unlike regular triangles, the Trigon has inward curves at each point.

Then we return to the Quinton. It’s my favourite shape, not just because of its form, but because of a personal connection—I had a dog named Quinton. He’s no longer with us, but this shape reminds me of him, and I often share that story with students. These moments of memory and connection help us relate to the shapes beyond their form.

U-shape wood cut by Brittney

And because we like to have fun in the classroom, I try to make the learning joyful and playful. I’ll say, “This is the U-shape—the mustache shape!” I have so many photos of students holding it under their noses like a mustache. These little moments of laughter and imagination help us build trust and make the learning feel alive and connected.

Walking together

Being a lifelong learner means walking alongside others—students, educators, families, and community members—and understanding that we each carry something important.

For me, art is a way to pass on teachings, deepen our connection to land and culture, and create joyful learning spaces. These shapes hold more than lines—they carry language, memory, and story.

The more we learn together, the more connected we become. And when we approach each other with curiosity, care, and humility, we begin to build a shared sense of belonging—one shape, one story, one step at a time.