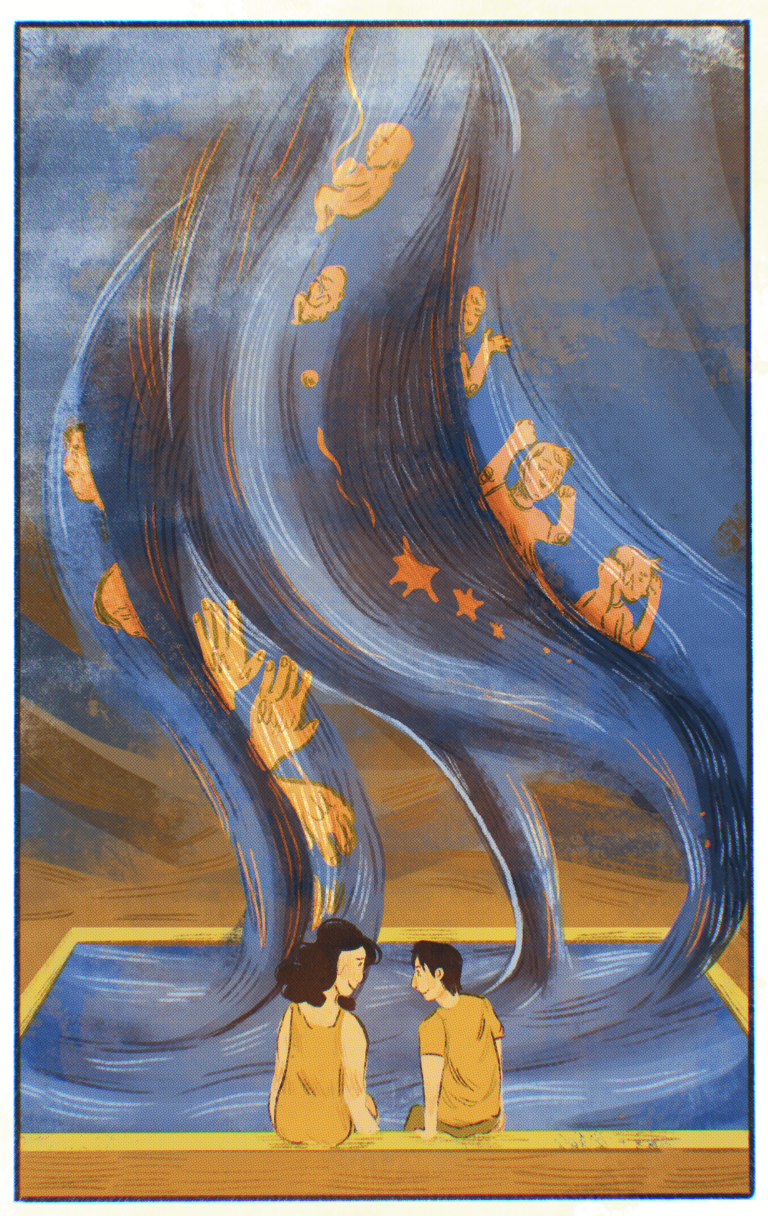

Artwork from Treading Water by Katherine Chupik-Hall

Comics are an effective medium that presents complex ideas in an easily understandable way. They use a combination of art and text to engage readers, making them a valuable tool for education, entertainment, and social commentary.

According to multiple members of the Arts community, comics have gained prominence as a powerful tool for knowledge dissemination and have successfully addressed complex issues to a diverse audience. With the ability to convey nuances that may not be as easily transmitted through traditional educational channels, the visual graphics in comics have emerged as a compelling medium for effective communication.

Director of the UBC Comics Studies Cluster and Assistant Professor of Teaching in the Department of Central, Eastern, and Northern European Studies Dr. Elizabeth Nijdam provides insight into how comics can convey complex ideas and difficult subjects. Dr. Nijdam describes that the comic format draws the attention of various audiences and ensures that subject matter that is otherwise difficult to digest reaches a diverse audience. Artistic representation is subjective and reflects human experience.

“The power of comics lies in the form’s combination of text and image, which offers opportunities for representation of experience often elided by verbal description. For example, comics can express silence in ways impossible by the written word.”

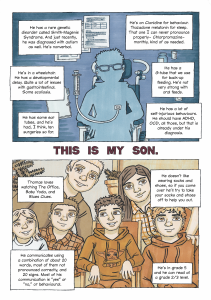

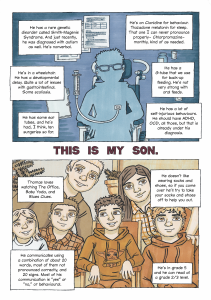

Comic page from “This is my son” by Jonathan Dalton.

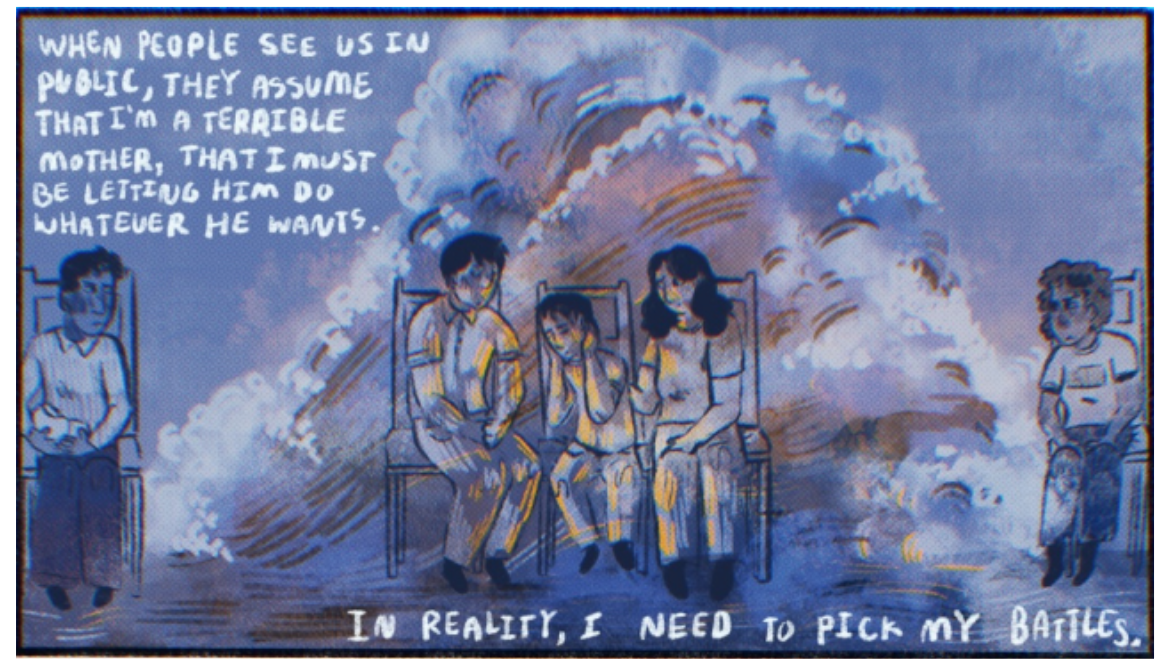

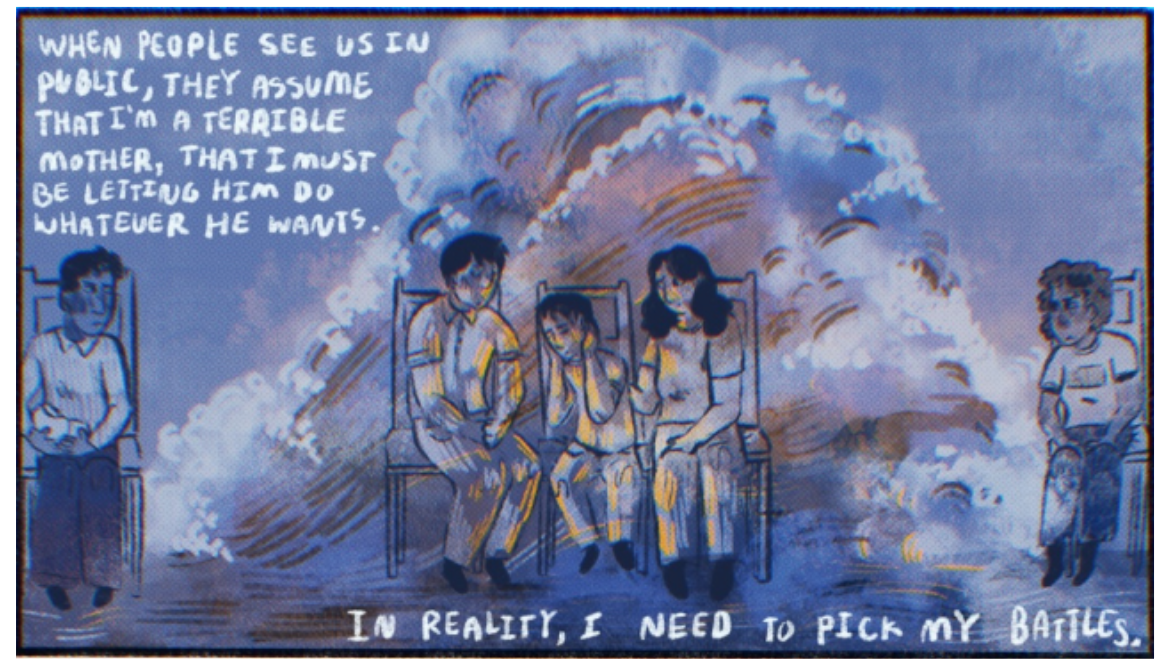

Dr. Nijdam explains that comics frequently use visual metaphor, artistic style, composition, and layout to augment, complement, or complicate the story. Using these visual references, comics can build stories upon stories, deepening and complexifying the reader’s engagement with the narrative.

Creative Writing Assistant Professor and cartoonist Sarah Leavitt loves the form of comics because it offers many opportunities for layered and complicated storytelling. Leavitt illustrates that comics are not simply words illustrated with images but involve blending words and images to create something new. A simple example she describes is an image of a character who looks angry but whose dialogue, in a speech balloon, says something like, “That’s fine with me.” The image complicates the meaning of the text and introduces questions and doubts for the reader.

“Cartoonists have so many tools they can use to shape the reader's experience. Imagine the possibilities when you introduce metaphorical imagery to heighten emotion or combine text with abstract imagery, using colour, shape or line quality to convey meaning.”

Comic page from “Sammy” by Elsbeth Dodman.

Leavitt was previously a Co-Lead at the UBC Comics Studies Cluster and currently teaches multiple Graphic Forms courses at the School of Creative Writing. Over the past 12 years, she has observed that students can use comics to explore stories or ideas that they haven’t been able to access in any other way. This includes anything from deeply personal stories that emerge through drawing exercises to surreal fiction from experimenting with collage.

The UBC Comic Studies Cluster was established to provide a platform for students and researchers interested in Comics Studies. The Public Humanities Hub initiated the cluster in 2022, and since its founding in Spring 2023, it has been actively involved in co-sponsoring event series, Comic Book Club events, and public-facing comics projects. The cluster has also moderated on-campus and international events, making it a growing hub for Comics Studies.

As part of our initiative to delve deeper into comics’ pedagogical and storytelling potential, we have conducted several interviews with faculty members and students who possess extensive knowledge and experience in this field. We have also had the privilege of hearing from individuals who are actively involved in creating comics.

Meghna Chatterjee

MA Student in the Department of English Language and Literatures

Meghna is pursuing her second year of Master’s degree. Her research work is focused on the intersection of formalist comics studies, critical race and gender studies, and migration studies. Her specific area of interest is the exploration of how the comic form can express borders, borderlands, and spatio-temporal movement.

What are your thoughts on approaching issues of representation and diversity in comics, and what role do you think the medium can play in the realm of education that advocates for inclusive representations of race, gender, and sexuality?

Longform comics that deal critically with racial, gendered and sexual subjectivities, educate via onto-epistemological investigations into these perspectives. Owing to its reliance on visuality, it emphasizes the importance of looking at subjects that defy hegemonic identity norms by controlling not only what we look at but how we look at them. When taught carefully, comics can stimulate ‘difficult’ conversations in classrooms and help younger readers become more critically literate. The visual-verbal art form possesses an incredible ability to transport us elsewhere, taking us to places, spaces and worlds that are not always accessible but are politically charged and demand critical conversations – I am thinking here about Joe Sacco taking us frequently into war-torn spaces, and so on– shifting conversations to geographies beyond our own, making us aware of cultures we don’t belong to.

How do you think comics can be used to convey complex ideas and difficult subject matter in a way that is accessible to a wider audience?

I wonder if comics advocacy is always tied to accessibility. While it is true that visual narratives are more easily consumed than hefty textual ones, I hesitate to say that it makes complex narratives necessarily “accessible,” in the same way that I hesitate to say that empathy is a required goal of difficult representation. Some of the most interesting works of comic advocacy have employed techniques that stop a reader and make them think otherwise. By inventing and incorporating new techniques, comic artists often force a reader to pause, think and imagine differently. From a reader’s perspective, this might evoke discomfort and invite them to sit with and consider change or difference.

Can you speak to any particular projects or collaborations that you have been involved in that demonstrate the power of comics as a tool for education and social change?

I was briefly involved with the “Remember” Comics Project by the UBC Comics Cluster in collaboration with the Homalco First Nation. The project funds Indigenous artists across BC to draw out episodes of the “Remember” podcast, where Homalco Elders talk about daily life in the Bute Inlet. Podcast episodes deal with several aspects of Homalco life, including their history, local customs, and storytelling practices. Although still in the works, I think the project possesses fantastic potential and will fit wonderfully into the growing tradition of Indigenous graphic literature in Canada.

Gavin Paul

Instructor in Arts One and Department of English Language & Literatures

Gavin has a keen interest in graphic novels and has published his work in various publications. He has written on graphic novels, comic book literature, and literary responses to 9/11. Some of the publications that featured his work include American Periodicals, European Comic Art, and The Encyclopedia of Comic Books and Graphic Novels.

Can you tell us about your experience using comics as a method of storytelling and how you find it effective in education?

One of the virtues of employing comics in education is their incredible versatility. You can certainly study material that has influenced popular culture, such as Watchmen or The Dark Knight Returns; this kind of traditional fare can often be a useful introduction to comics since it is often incredibly rich and rewards your close attention.

My most memorable experiences with comics in the classroom involve genres that many students might not associate with the medium: memoirs like Alison Bechdel’s Fun Home, war reportage like Joe Sacco’s Safe Area Gorazde, or historical fiction like From Hell. Once your class has spent some time thinking about how comics can be put together and how they signify, then from that baseline of knowledge, you can explore in any number of directions.

How do you think comics can be used to convey complex ideas and difficult subject matter in a way that is accessible to a wider audience?

I’ve found myself telling students lately that I appreciate how comics require you to “lean in.” Comics are hard work to make and they are just as difficult to read. In reading comics, one has to slow down and appreciate just how much information is in every panel, every sequence, and every page.

I’ve recently finished Joe Sacco’s Footnotes in Gaza, and what struck me was the humbling detail that Sacco etched into every face. There’s honesty in Sacco’s portrayal of everyone he interviews for that book, every historical figure he imagines. There is something about a detailed hand-drawn face or even a map–my awareness of the time and energy it took to produce it–that gives it a unique signifying power. Whatever your politics or feelings about an intractable situation in the Middle East, slowing down and leaning into Sacco’s work is a productive way to engage with a horrifying situation. Sacco’s book doesn’t solve anything; he doesn’t tell you what to think, but rather, his book makes you aware of what you need to be thinking about.

What are your thoughts on approaching issues of representation and diversity in comics, and what role do you think the medium can play in the realm of education that advocates for inclusive representations of race, gender, and sexuality?

I believe comics foster empathy. Literature can share stories in the first person (“I”), but comics can take this a step further and invite you, the reader, to more fully occupy another person’s perspective. Beyond hearing a story told in a unique voice, comics can encode other layers of information on the page that enrich one’s understanding of other’s lived experiences. An artist can construct a panel in such a way that you see the world through someone else’s eyes. This kind of intimate participation on the reader’s part has tremendous potential for inclusive representation. Film can also position you, the viewer, in the place of another, but watching a film is a relatively passive experience: images on a screen wash over you while you sit in a darkened theatre. Comics require continuous, active, imaginative engagement as you move from panel to panel. There’s no other form of reading quite like it.

Dr. Strang Burton

Associate Professor in the Department of Linguistics

Dr. Strang Burton focuses on undergraduate education and is currently working on a graphic novel about first-year university life. For many years, he worked with elders and community members to document the Upriver Halq’emeylem (Halkomelem) language, working for a community-run language revitalization program, the Stolo Shxweli Halq’emeylem Language program, at the Stolo Nation, in Chilliwack, BC.

How do you think comics can be used to convey complex ideas and difficult subject matter in a way that is accessible to a wider audience?

First, when we talk about conveying complex ideas, combining textual with parallel visual presentation of concepts and stories is very powerful. This is not anecdotal or impressionistic: educational psychologists like Richard Mayer have found consistently in controlled empirical studies that when words and pictures are presented in parallel, learners can more efficiently construct verbal and visual models and build connections between them. It is crucial that the two streams convey two different sides of the same coin. For example, a purely decorative illustration can detract from the processing of ideas, something which not all comic presentations get right; however, when done correctly, the effect is consistent and strong. We feel it, too, of course, in the ease with which we process graphic novels and comics—one can hardly put them down without finishing them, but what the studies show us is that this is not just because the content is necessarily ‘simple,’ or we find pictures ‘fun’—it fits with how our brains learn best, regardless of the inherent complexity of what we are learning.

Second, it’s also worth discussing comics’ power in presenting emotionally difficult subjects. My own experience as a reader is that the format can be deeply humanizing and that it offers a more personal connection between author and reader in a way that changes the emotional impact. This personal connection can make emotionally troubling subjects easier to approach in a truly empathetic way.

Can you tell us about your experience using comics as a method of storytelling and how you find it effective in education?

My current work at UBC is focused on undergraduate education. Still, for many years, I have also worked on language documentation and the development of pedagogical materials for a community-run language-revitalization program for a local endangered language, the Sto:lo Shxweli Halq’emeylem Language Program at the Sto:lo Nation. As our development methods there progressed, it ended up that storytelling in a comic format became a big part of both our initial documentation and the teaching materials we developed from the Elders’ language—and I think the materials in this format were very successful.

On the documentation side, we developed a practice where we would ask the Elders to narrate storyboarded sequences, some of them targeting particular grammatical constructions and others based on narratives the Elders had already shared from their personal histories. For instance, stories about growing up in a longhouse. The Elders then narrated the stories in Halq’emeylem, and a number of the stories were then professionally illustrated by local community artists. Some examples (though far from the whole collection in our archives) can be found on the Sto:lo Shxweli Halq’emeylem Language Program website.

Can you speak to any particular projects or collaborations that you have been involved in that demonstrate the power of comics as a tool for education and social change?

The storyboard methodology for collecting materials proved very useful as a way of collecting linguistic research data, especially when exploring highly context-sensitive phenomena. I started doing this myself in my work at Sto:lo and some of my colleagues at UBC, including Dr. Lisa Matthewson, worked with me to develop the idea as a methodology for linguistic fieldwork in general, and this methodology has since become I think quite a popular methodology among many linguistic fieldworkers. Some materials from projects I worked on in this area are at Totem Fish Storyboards and Lisa and I have started an online journal Semantic Fieldwork Methods that publishes papers that explore innovative techniques for linguistic elicitation, including many papers that use the storyboard technique.

Dr. CW Marshall

Professor in the Department of Ancient Mediterranean and Near Eastern Studies

Dr. CW Marshall has a wide range of interests, including popular culture and the reception of classical literature. He has co-edited two volumes on how comics portray the ancient world, as well as on The Wire and Battlestar Galactica.

Can you tell us about your experience using comics as a method of storytelling and how you find it effective in education?

My work in comics studies often considers the representation of the ancient Mediterranean world in comics, considering the lasting influence of ancient myth and literature on modern texts. What is wonderful is that the analysis of comics can then be projected onto ancient evidence as well. For example, I’ve used the vocabulary of comics studies to interpret Athenian and South Italian vase paintings. Every discipline develops its own analytical tools and apparatus, and as comics studies develop as a scholarly discipline, its tools will be used more widely.

Can you speak to any particular projects or collaborations that you have been involved in that demonstrate the power of comics as a tool for education and social change?

There continues to be prejudice and misunderstandings about the medium of comics, which academic legitimacy helps to erode. Comics can be transformative as students come to see literature and narrative develop in new ways. Within my field, comics help break down the received colonial and elitist associations that still persist. In democratizing access to ancient narratives, and reframing them in new media with new interpretations and values, comics can innovate and challenge existing institutional structures.

My work with George Kovacs involves editing two collections on Classics and Comics and other projects, including a paper we delivered last year on Mari Yamazaki’s manga, Thermae Romae.

In your opinion, what are some of the most pressing issues facing the field of comic studies, and how can UBC work with local communities and artists to address this challenge?

It would be wonderful to see Comics Studies develop as an academic discipline at UBC — introducing an interdisciplinary minor, for example, would be a great first step. For that to happen, buy-in from the faculty and individual departments would be needed, to ensure that there are always enough courses offered every year to assure students can complete the program. That is something I would love to help develop.

Jennifer Nagtegaal

PhD Student in Spanish at the Department of French, Hispanic and Italian Studies

Jennifer Nagtegaal conducts research in the intersection of cultural studies and contemporary Hispanic visual culture, with a focus on comics studies and animation studies.

Can you tell us about your experience using comics as a method of storytelling and how you find it effective in education?

Comics are not only an effective means of storytelling, but they are also an effective means of communicating an array of information in education as well as scholarly inquiry. This phenomenon is often referred to as comics as scholarship. Entire theses have been composed in comics form. Nick Sousanis’ Unflattening in 2015, the culmination of his Doctor of Education program at Columbia University, being a trailblazer in this regard, with more recent and local attempts seen in Vancouver-based artist and secondary art teacher Meghan Parker’s Teaching Artfully, which was a final step for her MA in education from Simon Fraser University in 2018.

Although I am not personally attempting this feat in my dissertation on so-called “expanded comics,” I have used comics as a means of introducing myself to my students in various courses that I have taught or assisted in teaching, and as a means of conveying my research and its impact at various stages of my dissertation writing process. For example, the proposal defence or for conveying its scope and impact to funding agencies like SSHRC, and I anticipate, my doctoral defence in some way shape or form. Plus, with graphic design platforms like Canva, even the artistically challenged like myself can engage in storytelling with comics for educational purposes! Having students tell stories through comics can be a very effective tool for assessing their learning. Comics are about showing as well as telling, and striking the right balance between the two. Creativity and concision go hand-in-hand.

How do you think comics can be used to convey complex ideas and difficult subject matter in a way that is accessible to a wider audience?

The more complex the idea, and the more difficult the subject matter, the more relevant comics are for conveying these ideas and issues to audiences. Comics are a complex medium. This does not mean that every comic is complex, or conveys complex ideas and experiences, but they have the potential to be so and to do so. They are widely accessible because there are multiple entry points for engaging with a comic: readers can begin by focusing on either the images or the text (when present), or perhaps even general impressions of the artist’s drawing style, the colouring, the arrangement of the panels on the page, the story’s possible intertextuality or intermediality, and if we are talking about multimedia comics or digital comics the aural elements (i.e., music, sound effects and speech). All of these intermingle and interact in the telling of a single story, which the reader actively participates in by weaving together meaning.

But when considering the effectiveness of comics in education, we can bring up another type of accessibility: making course texts easily digestible for all students. Digital comics (whether they are PDFs of comic books and graphic novels or actual webcomics) are increasingly being made with accessibility in mind (i.e., screen-reader compatible), but there is also the fact that the growing form of webcomics are often free and can be accessed from anywhere, by anyone!

What are your thoughts on approaching issues of representation and diversity in comics, and what role do you think the medium can play in the realm of education that advocates for inclusive representations of race, gender, and sexuality?

The graphic novel form, which has long been dominated by autobiographies, memoirs, and biographies, has emerged as a vibrant vehicle for representing diversity, identity, and culture. In Spain, for example, the representation of personhood – experiences of aging, of neurodiversity, of gender and sexuality, of regional and national identities and of belonging – has been one of the most salient characteristics of this nation’s graphic novel movement that has been unfolding for the better part of the last two decades. I know this is also true of much current North American comics creation. Incorporating comics for inclusive education seems like the most natural thing to do, simply because diversity is a narrative that we see time and time again from comics creators. There is no shortage of meaningful texts to choose from!

This requires us to equip students to engage critically with texts. In the same way that effective film analysis often requires providing students some basic film terminology and perhaps even some film theory, to truly understand and appreciate these inclusive representations, we should introduce students (even if briefly so) to some comics terminology and theory.