Dr. Christoper B. Patterson. Photo: Nathalie Green

Much of Dr. Christopher Patterson’s work examines the intersection of race and video games—across both game development and play. We asked about what drew him to this topic, how he views the role of his own identity in his research, and about some of his key projects, including two podcasts that spotlight new works on Asian Studies topics.

Dr. Christopher B. Patterson (he/they)

Associate Professor, Institute for Gender, Race, Sexuality & Social Justice

Dr. Christopher B. Patterson is an Associate Professor at the Institute for Gender, Race, Sexuality & Social Justice and the Asian Canadian and Asian Migration Studies program at the University of British Columbia. His research focuses on transpacific discourses of literature, games and films through the lens of empire studies, queer theory and creative writing.

Chris lives and works on the traditional, ancestral and unceded territories of the xwməθkwəy̓əm (Musqueam), Sḵwx̱wú7mesh (Squamish) and Səl̓ílwətaʔ/Selilwitulh (Tsleil-Waututh) Nations.

You’ve done a lot of work studying the intersection of race and video gaming. What was the genesis of your research in this area, and how has your focus changed since you started?

I started reading academic books on video games as a student in Las Vegas because my air-conditioning had gone out in my apartment and it was over 100 degrees Fahrenheit outside, so I spent every day in my university’s library. I came across books on video games, and taught myself all about them. About half a decade later, in graduate school, I still had no mentors in game studies, but I realized how angry these books about games made me. They seemed full of hyperbolic idealism, and very presumptuous on what games were, who made them, and who played them (mostly white straight men, or Japanese men). Anger, as usual, is great fuel for writing and research.

What’s the essence of your findings thus far?

Similar to the way we read Victorian literature to understand the British empire, we can also read video games as artistic expressions of particular forms of colonial power and imperial reach. As products of Japanese and North American relations, games are (for North American audiences) “Asiatic” forms of media that express the racial anxieties within and between Asia and North America (as well as their hereto-patriarchal norms). As technological innovations, they express the tensions of new technology, as well as the vast exploitation of manufacturing and resource extraction.

If we can come to respect games as powerful art forms, we must too take them seriously as a vastly influential (and vastly profitable) form of media that has had incredible impacts on the way we view the world, and each other.

“Similar to the way we read Victorian literature to understand the British empire, we can also read video games as artistic expressions of particular forms of colonial power and imperial reach.”

Tell us about some of your recent projects.

I and others organized the UBC “Games in Action: interactivity / activation \ activism” conference held last fall at the Chan Centre. For that event, we brought together game designers, artists and scholars to examine the impact of video games on our social and political world (we also had an arcade!). Our hope was to inspire audiences to consider the “actions” that games make in understanding marginalization and structures of power. We explored how games act upon us and through us, and how they compel us to take action for ourselves.

Also, I’ve been developing my own video game, Stamped: an anti-travel game, that’s going to be coming out in June. The game is based on my first novel, Stamped: an anti-travel novel, which I wrote when I was traveling around Asia and saw that there were no novels I could find about young, racialized and queer travellers. So I wrote that novel myself. However, there’s still no video game about these topics either, so I decided to make the novel into a game!

I’ve been designing the game with a team of five UBC students and staff, and we shared a pre-release version of it at the conference. That was a real learning experience for me, to see people playing my own game, in person. It gave me an understanding of how my own ideas in a game can impact players, and revealed the power that games can have to move emotions, as well as to frustrate. For example, players really connected with the way these down-and-out characters travelled to deal with traumas, or with not having a “home.” The characters also talk about race, gender, and colonialism in a very in-your-face kind of way, which is something that happens among travellers, but is also so rare to see in video games.

STAMPED is a forthcoming video game by Dr. Patterson and several UBC collaborators. Image: Braedyn Lemckert

Currently you’re co-editing an anthology called Made in Asia America: Why Video Games Were Never (Really) About Us, contracted with Duke University Press. What is being implied in the title, and how does the book support its premise?

The title is a bit coy, though it does pack a lot of ideas. First, myself and my co-editor Dr. Tara Fickle (University of Oregon) both identify as Asian North American, and we both wrote books about Asian America and game studies (mine was Open World Empire: Race, Erotics, and the Global Rise of Video Games, with NYU Press). All the contributors to the collection—fifteen scholars, twenty game makers—also identify somewhere in relation to Asia America (some are from Canada, Hawai’i), and we all see games as a form of media that has been made possible through the shared design and technology of Asia and North America. Most game studios, designers, and players, have been located in what’s typically referred to as “Asia” or “America”.

Second, with this work, our ambition is to shape games as a means of understanding the world-making (and race-making) activities of all digital media, which is why we invited game scholars, game makers, and game players to contribute.

Finally, we also want to de-center our own position as North American game players. North Americans make up a minority of game players (around 25 per cent), and we are not the sole target audience for most games—so why should all our studies about games be about us?

Many years ago you started a podcast, New Books in Asian American Studies, spotlighting works that may not be getting attention from mainstream media. How did this project begin, and what’s been the most interesting aspect of this effort?

In 2013, I wrote an angry letter to the guy who runs the New Books Network, Marshall Poe, asking why there was not a podcast on Asian American Studies books. He said no one had asked him yet, and that I should do it, since I was clearly so passionate about it. Thus the podcast was born! I began the first episodes during my PhD, but it really took off after I moved to Nanjing, China, and later to Hong Kong.

While abroad, hosting the podcast gave me an excuse to carefully read Asian American Studies books, to speak with their authors, and to push their research to include various political and social events happening in the world.

On that last point, I also founded The Journal of Asian American Studies Podcast in 2021, where I interview authors and organizers gathered around particular themes or events. This podcast goes further in the direction of diverting knowledge toward political action. Our second podcast, for example, was a response to the 2021 Atlanta spa shootings, where we brought together scholars and activists to discuss the historical causes and possible modes of active response.

Can you tell us more about your identity, and what makes you proud of your Asian heritage?

I’m mixed Filipino, white, and a bit Chinese, and I come from a family based in Hawai’i that includes Filipinos but also Kanaka Maoli (Indigenous Hawaiian), Black, Japanese, and Chinese heritage. My recently departed wife (Dr. Y-Dang Troeung, Associate Professor, Department of English Language and Literatures, UBC) was also Cambodian (Khmer) and Chinese, so our five-year-old son inherited all our mixtures. With mixture comes distancing, but it also has given me a unique, critical eye. Since no community has ever accepted me as “fully belonging,” my default position is one of inquiry and jest. So I’m an outsider who shows love and care in my own way.

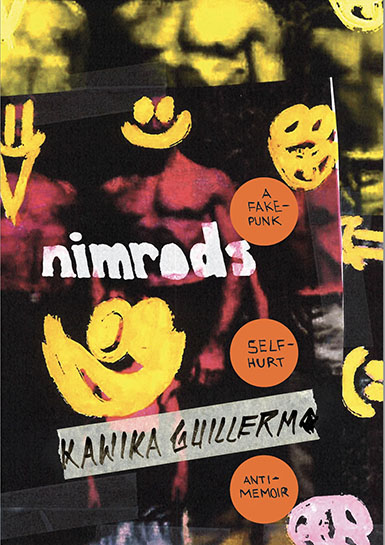

To try and grapple with all this, I write stories and poems under my matrilineal name (my mother’s last name and the name she wanted for me), “Kawika Guillermo.” As Kawika, I’ve published two novels, and most recently, I have a prose-poetry work coming out in August from Duke University Press (Nimrods: a fake-punk self-hurt anti-memoir). I’m hoping the book makes an impact on how we understand the political and personal vagaries of mixturedom.

Nimrods is a book by Dr. Chris Patterson writing as Kawika Guillermo. Image: Chris Patterson and Aimee Harrison

How does the current climate and discourse about the rise of anti-Asian racism impact your work? Are there elements that have shifted your motivations, objectives or approach?

First, I think it is important to specify that this specific rise is not merely “anti-Asian,” but focused more on China and people of Chinese descent due to COVID-19. It’s an important context to point out, not only because East Asian communities often stand in for “Asia” (the ripples of colonial relations and histories), but also because we cannot begin to combat anti-Asian racism now without also grappling with the disturbing ways we still perceive of China and Chinese immigrants as political, social, and economic actors.

My co-written essays with my late wife (Y-Dang Troeung) attempt to grapple with this by focusing on the way some depictions of China (and Chinese North Americans) play the role of “organic China,” further increasing racism toward an “inorganic China.” In my own work on video games, I focus more on “pro-Asian” types of racism, or the racism that emerges through what we believe is “good” stereotyping—for example: the soft, beautiful, wise, playful, erotic and exotic type of Asian fetishism. To me, this is how anti-Asian racism hides in broad daylight: how it codes “good Asian” to imply that there’s also a definitive “bad Asian.” And it’s everywhere.