Photo by Martin Dee

Riannon, also known as Tlekamiidext, was gifted her traditional name by her grandfather and was pronounced by her grandmother. She is from the Nlaka’pamux territory, but her lineage is Nlaka’pamux and Tsimshian, which is represented through her ardent interest in pictographs and land-based art.

When living on reserve over the summer at the Nicomen Indian Band, Riannon enjoys spending time outdoors, camping, and foraging with her family. Her art practice is unique and sustainable, reflecting inspiration from combining interior Salish and coastal artwork practices, showcasing her bloodline and connection to both communities. Riannon is a fourth-year student, majoring in the First Nations and Endangered Languages program with a minor in Anthropology.

We interviewed Riannon about the multimedia artwork she created for the Indigenous Symbols and Signifiers initiative, which answers the question: What symbols represent belonging in your culture? Here’s what Riannon has to say.

About Riannon and her inspiration

The Nlaka’pamux territory is just in the canyon. It’s got a bit of a border from south of Lillooet to just over the U.S. border, and there are a lot of pine trees. We’re in the hotspot—it gets very warm in the summer. It gets to about 46°C (I think the heat record was), and we actually lost our hometown in 2021, so it’s finally being rebuilt slowly.

The Tsimshian—I’m from Rose Island in Port Simpson. That’s where my father’s side of the family is from, and it’s very, very much like an island. There are huge cedars and a lot of huckleberries and blueberries. It’s really nice there; I like to visit in the summer.

We do a lot of hunting and harvesting together. And it definitely helps a lot, especially when you come to Vancouver and you’re used to like small town areas, I always miss going home and camping, hunting, and fishing.

Riannon's artwork

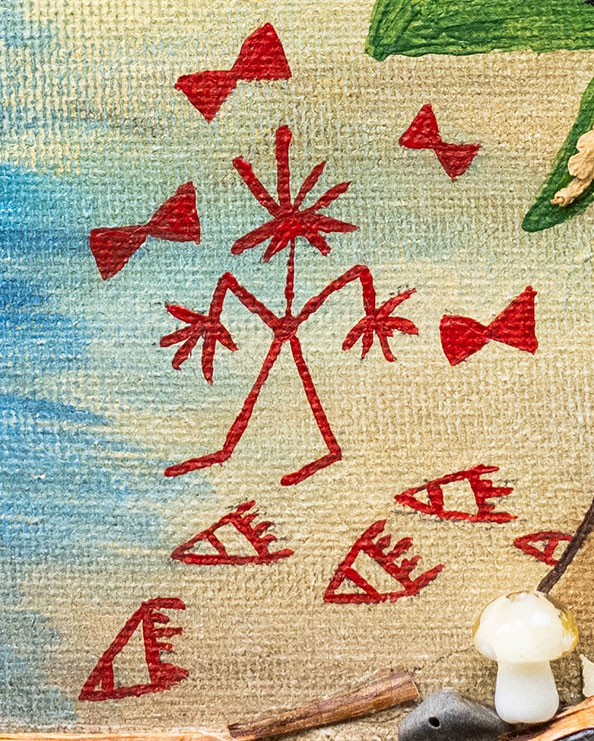

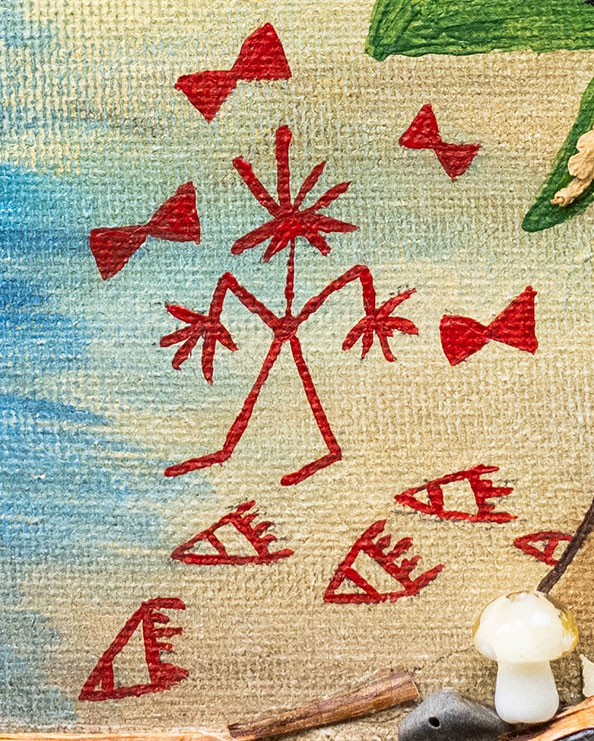

Original artwork of Riannon titled "Rooted" which was inspired by her Nlaka’pamux and Tsimshian heritage.

Riannon's artwork

Original artwork of Riannon titled "Rooted" which was inspired by her Nlaka’pamux and Tsimshian heritage. The sides are lined with cedar bark.

Birch bark

Riannon's grandparents harvesting birch bark. Photo provided by Riannon.

Beadwork

"I made the earrings throughout my four years of beading." Photo provided by Rianon

Soapstone carving

"This soapstone carving is an abstract Buffalo I made for my dad." Photo provided by Riannon.

Fishing

Riannon's grandfather unhooking a fish. Photo provided by Riannon.

Black bear

A scene from Riannon's summer trip back to Lax Kwalaams also known as Port Simpson. Photo provided by Riannon.

Kayaking

A scene from Riannon's summer trip back to Lax Kwalaams also known as Port Simpson. Photo provided by Riannon.

Northern lights

Photo provided by Riannon

Riannon's mountain views

"Most of the mountain pictures are of my home at Nicomen or in Town at Lytton (roughly 15 minute drive apart)." Photo provided by Riannon.

Riannon's mountain views

"Most of the mountain pictures are of my home at Nicomen or in Town at Lytton (roughly 15 minute drive apart)." Photo provided by Riannon.

Rest area between Terrace and Prince Rupert

A scene from Riannon's summer trip on the way to Port Simpson. Photo provided by Riannon.

Materials from the land and sea that hold memory

Heavy rain

To start off, my name is on top of a cedar—it was a little cedar-woven basket, and my mom took it apart for the project. Tlekamiidext is my traditional name in writing that my dad helped me do, and it means “lots of rain” or “heavy rain.” That’s why I have the cotton balls and the little crystals to kind of represent the rain falling down onto a great big cedar. The cedar tree has a buckskin hat, some copper, and abalone shells that represent both my Nlaka’pamux and my Tsimshian sides. The cape was done with a leather backing that I used to make earrings with, and I shaped it to kind of go with the tree.

At the bottom of the tree, I did an ovoid with triangles on the side. They’re not traditional Formline work, because I tried to mimic a raven’s beak, and it represents my grandpapa Maleford and Allen. The trunk has a pictograph that means “life,” and that’s the whole point of the presentation: it’s kind of like a circle, and it’s consistently flowing, like how the water rises from the ocean and then rains down onto the trees.

Sun Man, grizzly paw prints, and butterflies

The bear here with the grizzly paw print is my Gran; her traditional name is Sitting Grizzly, so I thought it’d be nice to acknowledge her. Over here is the Sun Man, who represents my grandpa, Wes, who helped name me. I wanted to represent both of them in the painting. The little butterflies are from the ancestors basketry work passed on through generations. It represents me, my siblings, and my mom. The cedar roots, I had the intention of them coming from the tree and going into the ocean to show that connection.

Over in the ocean, we have the dentalium shells, which have a very high trade value for the Tsimshian. Those [shells] were actually also given by my mom. She got them—I think—from a store, 4 Generations Creations, and she’s an Indigenous-owned business that supports other Indigenous artists as well. And here’s the killer whale’s dorsal fin. I originally was going to do it more bold, but I kind of like the transparency of it. I was supposed to be adopted into a killer whale house, but I ended up not being adopted. So, that’s also what the butterflies represent—because when you don’t have a house, you’re actually considered a butterfly.

“The trunk has a pictograph that means 'life,' and that's the whole point of the presentation: it's kind of like a circle, and it’s consistently flowing, like how the water rises from the ocean and then rains down onto the trees… So the pictographs—there are a lot of them—to mesh together the Nlaka’pamux and Tsimshian artwork.”

Fusing traditions and honouring ancestry

For the pictographs, I used red sinew and red bugles to add some texture to it. The sinew comes from the deers—which we call smíyc—and it represents the mountains in the basketry work. I didn’t know if I wanted to paint the sides, but since my mom and I came up with the name “Rooted,” I figured I might as well add the cedar roots on the sides, too.

What really drew me to it was the combination of pictographs and the coastal work, because I’ve never really seen that done. So the pictographs—there are a lot of them—to mesh together the Nlaka’pamux and Tsimshian artwork, because with Tsimshian artwork, they do a lot of ovoids and more fine line work.

For the background, I used a bit of watercolor and acrylic to show a stormy sky. For the ocean, I used a bit of blue and tried to keep this part bright so that you could see it. For the pictographs, I chose red, because that’s what you’ll see when you go on a Stein Valley Trail hike or when you’re in the area and you find them

Cedar roses

I do a lot of beadwork. I’ve done earrings such as fringe earrings and ones with stiff felt. I’ve also tried cedar basket weaving and made a cute little one. I want to get into cedar roses and do more work with that. This spring, I’m hoping to go harvesting with my mom, and she’s going to show me how to make the baskets. Cedar roses are made with the outside of the cedar root.