The source images are from the Republic of the Philippines Presidential Museum and Library Flickr account.

When Dr. Leonora ( Nora) Angeles became a Canadian International Development Agency scholar at Queen’s University in 1989, she brought with her a deep interest in Philippine history and its economic relations with Canada. Propelled by the People Power Revolution of 1986 and its impacts, she continues to nurture her historical awareness and how it comes to play in the larger narrative of global politics and Canada-Philippine relations.

Dr. Leonora Angeles (she/her)

Director of the Institute for Gender, Race, Sexuality and Social Justice

Dr. Angeles, the newly appointed Head of the Institute of Gender, Race, Sexuality and Social Justice and Associate Professor at the School of Community and Regional Planning, is an advocate for thinking critically about the political landscape of the Philippines and the country’s history—especially since history has been used as a political tool to shape public opinion.

In June 2022, Ferdinand “Bongbong” Marcos Jr. was inaugurated as the president of the Philippines, almost four decades after his father, former dictator Ferdinand Marcos Sr., ruled the Philippines under martial law. Marcos Sr.’s brutal rule resulted in 3,257 known extrajudicial killings, over 30,000 documented tortures and 70,000 incarcerations. So how did his son manage to return to power? And what does that mean for the 110 million Filipinos and for the rest of the world?

The election came as no surprise to Dr. Nora Angeles. “The Aquinos* and other pro-democracy forces in the Philippines, unfortunately, have not seen the power of historical education in nurturing transformative social memories. But Bongbong Marcos, saw the power of re-writing history. Students who have been in the public school system know only one version of history [one that excludes the legacy of atrocities committed under the Marcos regime].”

We spoke with Dr. Angeles to better understand the inauguration of President Ferdinand (Bongbong) Marcos Jr., its potential effects on Philippine-Canada economic relations, and examples of similar antidemocratic patterns across the globe.

*The Aquinos: Benigno “Ninoy” Aquino Jr. was a Filipino politician who served as a Philippines senator and governor of the province of Tarlac. He was the husband of Corazon “Cory” Cojuangco Aquino who became the 11th president of the Philippines from 1986 to 1992. Ninoy helped form the leadership of the opposition towards late President Ferdinanrd Marcos Sr.

“Understanding our history is so significant to our cultural heritage retention and continuous learning as a people. Who we are, where we come from, what was done to us by us, and by others is so significant to understanding the structural and cultural forces that have shaped who we are as a people.”

Why should Canadians care about Bongbong Marcos being elected as president?

The Philippines remains Canada’s top country of interest largely because of the imported labour Canada has become dependent on since the 1980s. The Phillipines is the top source of new immigrants to Canada, and Filipinos are the third largest immigrant group. There’s almost 1 million Filipino Canadians now in Canada. We should be concerned about Bongbong Marcos’s election as President because the issues that Filipinos are going to be facing in the coming years have effects that spill beyond the Philippine national boundaries, which will certainly affect the daily fabric of Canadian lives.

First of all, Canada is among the Philippines’ top sources of remittances and I wouldn’t be surprised if international investors would shy away from the Philippines if the Marcos-Duterte administration falls short of its promises. There would be a massive deduction in foreign investments and trade in the Philippines that would make the government and state be even more dependent on remittances from overseas Filipinos. Overseas Filipinos represent about 10% of the total Philippine population—including our temporary foreign workers and overseas contract workers—who are keeping the economy afloat. During times of recession, economic crisis, and hardships, we can’t close our eyes to the hardships that our families back home [in the Philippines] are going to be facing. Whether it’s hyper inflation, the lack of social safety nets when they become unemployed, medical care, health care, and education.

The second reason is our own identity as Canadians. Canadians see themselves as global citizens who are interested historically in the promotion of democratic values, good governance, and human rights around the world. Not just through Canadian bilateral assistance and other public investments in these policy areas, but also through international development aid. The transnational economic, social and cultural relationship between Canada and the Philippines is growing deeper through these ties.

What will the impact of this election be for Filipinos and the global political landscape?

The presidential elections this year have become so polarizing for a lot of Filipinos in the Philippines and abroad because for many critical thinking Filipinos, there was a clear choice. It’s a decision between restoring and promoting democracy, human rights, and good governance—that had been put in place after the Marcos regime—and candidates tainted with histories of corrupt leadership and a return to Marcos rule Additionally, the concerns of political watchers over the impacts of the election; one example is how the country’s treasury was plundered by its own public servants under former President Ferdinand Marcos Sr.

This is not just the Philippines’ story. This episode is part of a broader pattern of the rise of populist authoritarian regimes in many parts of the world. There’s the Trump administration, Bolsonaro in Brazil, Erdogan in Turkey, certainly in other parts of Southeast Asia, the return of military rule in Thailand, and other parts of Europe. But there are bright spots in some places where authoritarian leaders have been defeated by those representing good governance, and the post liberal order. Maybe this is the time for Filipinos to be woken up from their complacency similar to what happened in Columbia where the narratives of truth and reconciliation commission were eroded and erased.

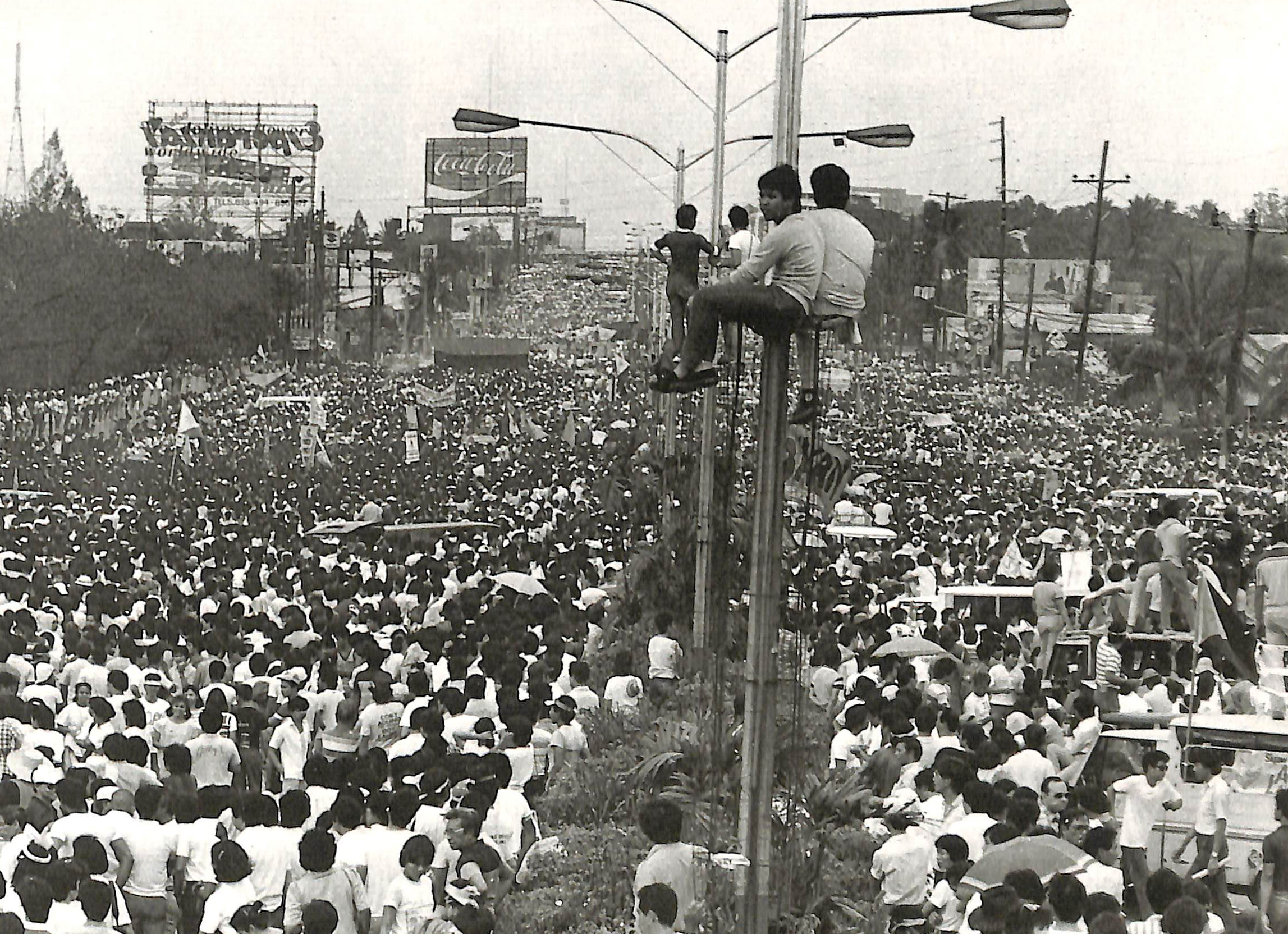

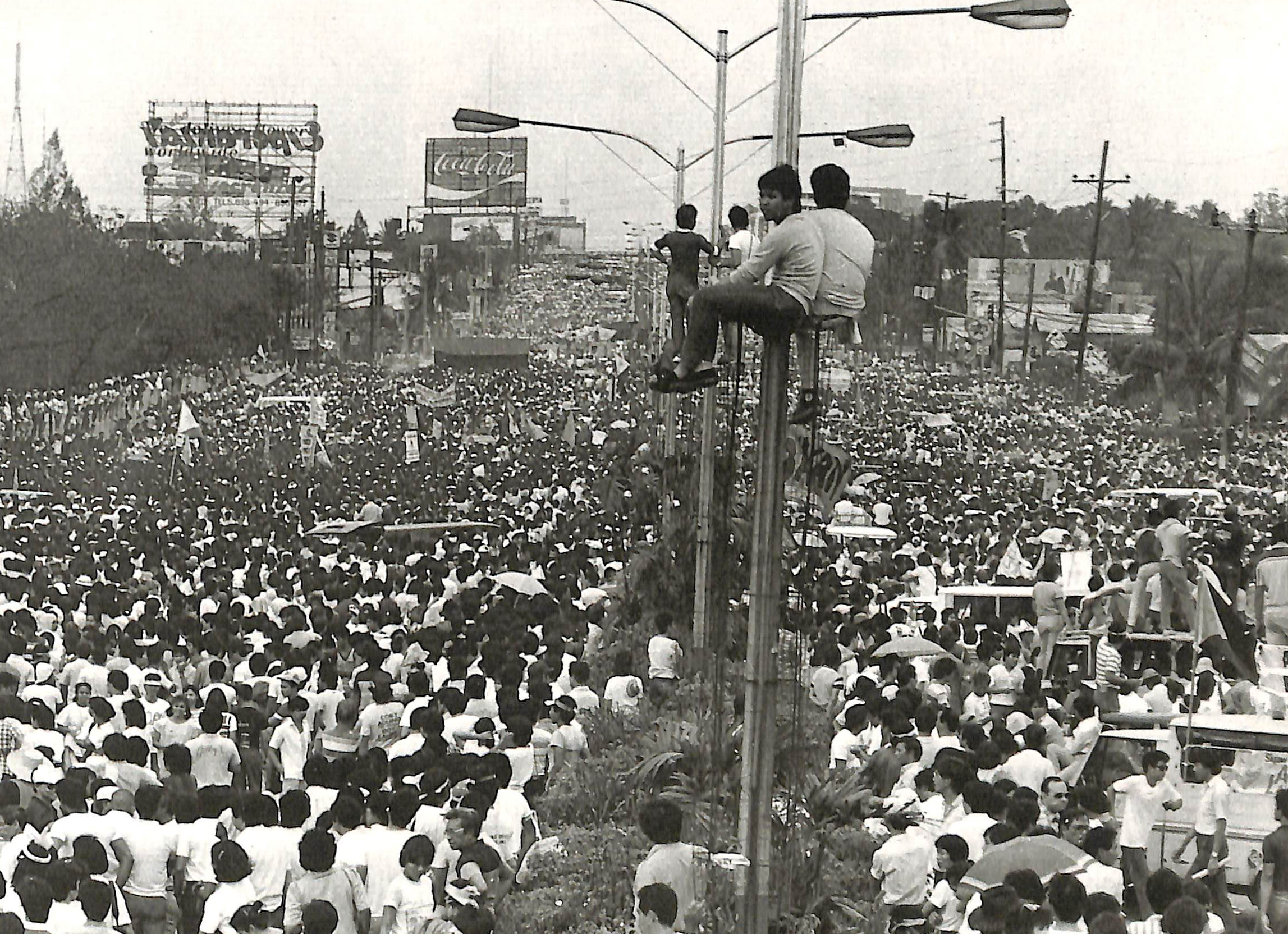

Thousands of citizens gather in the early afternoon of Feb. 23, 1986 for People Power Revolution, which overthrew the first Marcos presidency. The source image is from the Republic of the Philippines Presidential Museum and Library.

“Remember even before the downfall of the Berlin wall, before the post-socialist transition beginning in Poland in 1987, and the rest of Europe in 1989, there was the People Power uprising of the Philippines that brought down a 20 year dictatorship. We were the bright star of democracy.”

Related to this, what are you working on right now?

I am conducting research on post-national citizenships and Philippines-Canada economic relations. I’m looking at dual citizenships and those who hold a Special Resident Visa or a Special Investor Visa in the Philippines. Many of them are Canadians. We are certainly not blind to what is happening to our neighbours next door or to a country across the Pacific that is our top source for new immigrants and temporary foreign workers.

When Corazon Aquino—11th president of the Philippines from 1986 to 1992—went to Ottawa in 1989, two years after she delivered her important speech to the US Congress in 1987, I was a graduate student. That was the time when a sizeable amount of Canadian development aid went to the Philippines, largely to support two things. First, the (then) ongoing democratization of the government and the third sector—including the NGOs and women’s groups. Under Fidel V. Ramos all the way until Gloria Macapagal Arroyo’s administration, Canada has supported capacity building and human resource development of local government units across the country. It involved the training of the police, gender mainstreaming** to human rights—a whole list of initiatives that they presented. Canada offered real support to the post-Marcos administrations, particularly between 1986-2016.

**Gender mainstreaming: When all government operations, planning, implementation, monitoring and evaluation use gender disaggregated data. They consider the gender differential impact of the policies and programs that they have.

What kind of support are you hoping to see from the UBC community and beyond?

As a privileged place for education, UBC is a critical space for engagement and has a role to play within its own circles of influence—to continuously educate and open the eyes of the general public.

But support has to come from outside UBC because we’re just a tiny fraction of what’s needed. Filipinos, non-Filipinos, and all Canadians should know about the larger narrative of the destabilization of the postwar liberal order that we had come to appreciate in the Philippines. That includes the rights, freedoms, liberties, and human rights that we all enjoy.

We must challenge [elected political leaders] and hold them accountable to their electoralpromises. We could only hope the new Marcos-led administration and their allies will not disappoint the millions of Filipinos who brought them back to power.

Learn more:

- The World Should Be Worried About a Dictator’s Son’s Apparent Win in the Philippines (TIME)

- Randy David on Marcos restoration (GMA Network)

- Why the Marcos family is so infamous in the Philippines (BBC)

- Tortured by the Marcos regime, he just watched the family regain power (CBC News)

- The Triumph of Marcos Dynasty Disinformation Is a Warning to the U.S. (The New Yorker)